February seminars

8: Coming to grips with FamilySearch, WEA Centre Adelaide 10:00am

See the seminar program for more details.

TAS Convict Records Online

Tasmania's convict records can now be viewed online. The records of the convict system in Tasmania during the first fifty years of European settlement here were added to the UNESCO international Memory of the World Register in June 2007, recognising their historical significance. They can now be viewed at the AOT web site.

1911 Irish Census

The 1911 Census records for Antrim, Down, Kerry and Belfast are now available online from The National Archives of Ireland.

Queensland records

Records From Queensland: Public Service Employees, Classification Lists, and Cemetery Monumental Inscriptions collated by the QFHS can now be accessed via World Vital Records.

Surname dilemma

Determining surname-spelling variants is an essential part of family history. Many researchers fail because they are not prepared to accept the fact that the way they spell their name is probably a mere accident of history. They become locked into the current form of spelling. Standardised spelling is a relatively modern invention. When we realise that the majority of our ancestors were probably illiterate and relied on scribes to write their names, and those scribes wrote as they heard, then it is no wonder that we are faced with a multitude of spelling forms for what were originally the same names. Adding in prefixes like Mac just complicates things even further!

To top all that off, we have to accept that sometimes the name was just spelt wrongly. There could be a multitude of reason as to why this was so. How did the indexer of the 1895 Observer newspapers record the death of Mrs Mott of Mount Barker in their index as Moll?

Having realized that our name may be found in a multitude of forms in the records, our task is to second guess the possible formats and this article is designed to assist the process.

News

February seminars

TAS Convict Records Online

1911 Irish Census

Queensland records

Feature article

Surname dilemma

![]()

Adelaide

Proformat

5 Windana Mews

Glandore SA 5037

Australia

Tel: +61 8 8371 4465

Fax: +61 8 8374 4479

proformat@jaunay.com

Services

• Research

• Drafting charts

• Locating documents

• Seminar presentations

• Writing & publishing

• SA lookup service

• Ship paintings

Proformat News acknowledges the support by ![]() AWE

AWE

Because you not only need to address legitimate spelling variants but also plain errors, consider the following processes:

1.

Write down the name phonetically.

1.

Write down the name phonetically.-

Involve others in this process to see if they come up with other forms.

There is a large group of English names whose pronunciation belies their

spelling. Consider how the following surnames are pronounced and then

consider how some may have been recorded by unknowing scribes on hearing

them: Chalmondesley, Featherstonehaugh, St John, Derby, Stonehewerbird,

Dalziel, Marjoribanks, Fiennes, Beauchamp, Barroclaugh. (pronunciation

answers at end of article)

Most residents in the present day English town of Cirencester are no longer aware that the traditional way to pronounce their town's name is sis-sister!

-

W and K, like H, tended to be added or subtracted

at whim: Ray and Wray; Roe, Rowe and Wroe; Right and Wright; Nibbs and

Knibbs; Nott and Knott; Nutsford and Knutsford; Howell and Owell.

E has a happy knack of appearing at the end of some names as in Mark and Marke.

-

Jacksan, Jacksen, Jackson, Jacksun, Jecksan, Jecksen, Jeckson, Jickson,

etc.

-

There is a significant group of names that have had the letter s

added to make them easier to say in English. Many Welsh names have had

this treatment during the transition from the patronymic form as in William

William becoming William Williams.

-

Versions that retain a possible name are more likely as in Crips for Crisp,

but when searching databases there is the potential for unrealistic transpositions

to miss the checker. More than once I have located Juanay for Jaunay.

-

Consider names containing Gold as in Goldsmith, Goldstein and so on.

-

In the cursive hand of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries there are

certain letters that can be confused with others, certain strings of letters

that may prove difficult to decipher and certain personal handwriting

styles that can be difficult to interpret. If the name was unfamiliar

to the writer then there is a greater chance of error. Consider Jaunay

being recorded as Jannay.

I was used where we would use an initial J today.

-

G and J can be interchangeable: Garrard, Gerrard and

Jerrard.

-

The pronunciation of D and J can be almost indistinguishable, as in Dewsbury

and Jewsbury. Duberly sounds like Jubilee?

-

Scottish and Irish names starting with Mc are equally comfortable

as with Mac, Ma, M’ or with the prefix

dropped altogether as in Donald, McDonald and Macdonald! Similar treatment

applies to Irish and some continental names.

Not so obvious are names that developed (in some cases quite recently) from compound names. Consider Vongrasy originally von Grasy, Vanderlinden formerly van der Linden, Delisle was de l'Isle, Pritchard and Bevan from the Welsh, ap Richard and ab Evan.

-

The technique of applying the rules of Soundex to a name to assist

you in determining potential spelling variants is a useful tool, but using

such aids themselves can create another range of problems as the system

is by no means perfect.

Soundex

a phonetic algorithm designed in 1918 initially to index names by their

sound as pronounced in English is used by a number of USA government agencies

and the LDS Index, the IGI. When viewing USA Federal Census cards you will

see the Soundex code writing above the surname (a 1920 card is pictured).

You can determine the Soundex code for the surname under consideration—use

the web-based Soundex

generator. It is much easier to use a reliable generator such as this

because, while it is possible to generate a code manually, there are a few

traps for the unwary. The great feature of the Follow Soundex Converter

is that it gives you other names with the same score and some of these may

be variants of the name of interest.

Soundex

a phonetic algorithm designed in 1918 initially to index names by their

sound as pronounced in English is used by a number of USA government agencies

and the LDS Index, the IGI. When viewing USA Federal Census cards you will

see the Soundex code writing above the surname (a 1920 card is pictured).

You can determine the Soundex code for the surname under consideration—use

the web-based Soundex

generator. It is much easier to use a reliable generator such as this

because, while it is possible to generate a code manually, there are a few

traps for the unwary. The great feature of the Follow Soundex Converter

is that it gives you other names with the same score and some of these may

be variants of the name of interest.The Soundex code for a name consists of a letter followed by three digits: the letter is the first letter of the name, and the digits encode the first three consonants that survive the encoding process. Similar sounding consonants share the same digit so, for example, the labials B, F, P, and V are each encoded with the same value. Vowels can affect the coding, but are not coded themselves except as the first letter.

The correct value can be found as follows:

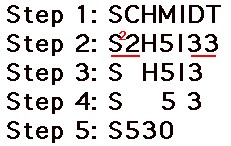

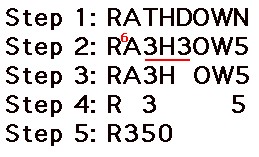

Step 1: Print out the name.

Step 2: Replace consonants with digits as follows (do not

change the first letter but note its value):

Step 2: Replace consonants with digits as follows (do not

change the first letter but note its value):B F P V these letters equate to 1

C G J K Q S X Z these letters equate to 2

D T these letters equate to 3

L this letter equates to 4

M N these letters equate to 5

R this letter equates to 6

Step 3: Collapse adjacent identical digits into a single digit of that value. It is this step that causes the most problems and you need to note the score for the initial letter in case it has the same value as the adjacent letter. See Schmidt example. You also need to be aware that if 2 letters of the same score were separated by W or H, remove the 2nd but if they were separated by a vowel, retain. See Rathdown example.

Step

4: Remove all the remaining letters after the first letter.

Step

4: Remove all the remaining letters after the first letter.Step 5: Retain the starting letter and the first three remaining digits. If needed, append zeroes to produce a string of three digits.

Using this algorithm, both Robert and Rupert return the coding R163. Lee produces L000, Jaunay J500 and so on. Note that if you want to use a non-English name then it needs to be spelt how it is pronounced in English!

Thus using a simple example, if the name has a Soundex code of W416 then we know the initial consonants could have included the combination of WLBR and this pattern will fit Wilber, Wilbert and Wilberforce, Wilbraham and Wilbram. You may not have considered the possible commonality of these three groups of names that in turn throw up even more names when considering their ancient forms like wildber was originally wildboar that in turn reveals wildbore and wildboer… Whereas Wilbert was Willbright and that meant William the smart one.

Soundex is not the only phonetic algorithm available to assist in this sort of background research and planning but it is the one with official recognition and is therefore the one you are most likely to encounter. You may like to consider using the following system, the New York State Identification and Intelligence System Phonetic Code [NYSIIS]. It has a code generator at: utilitymill.com/utility/nysiis. Other codes such as Celko Improved Soundex, Metaphone, Double Metaphone, Daitch-Mokotoff Soundex (D-M Soundex) are far more complicated.

When dealing with compound names like the previously mentioned Vanderlinden in the formulation of Soundex codes the single form should be considered along with the omission of the small prefix words.

Take a quiz and work out the Soundex codes for: a. LLOYD; b. PFISTER; c. FFRENCH;.d. JACKSON; e. DEVANTER f. REYNOLDS; g. TMYCZAK; h. LAUGHSON ...without using the online generator!

Because this is starting to become quite complicated, it is suggested that you consider preparing a table of the surnames of interest to you and spend some time recording all the potential variants and errors you may come across. Arm yourself with this list and ensure that when you search printed material you cover all options and when you search electronic records you use a range of wildcards to cover all the options. A seemingly simple name like Jaunay will eventually generate the following possibilities:

Jaunai, Jaunais, Jaunet, Jaunez, Jaune, Jauneau, Jaunard, Jaunasse, Jeaunais, Jeaunay, de Jaunay, Jainee, Jane, Jannay, January, and so on.

Quiz answers are:

Chalmondesley is pronounced chumley, Featherstonehaugh –

fanshaw, St John – sin-jen, Derby - darby,

Stonehewerbird – stonnerberd, Dalziel – dee-el,

Marjoribanks – marchbanks, Fiennes – fines, Beauchamp

– beecham, Barroclaugh – barrowcluff.

Soundex: a. L300; b. P236; c. F652; d. J250; e. D153/V530 f. R543 g.T522

h. L250

newsletter-leave@jaunay.com